Today I’m joined by Oscar Powell, the British musician and composer who records and performs under his surname: Powell. Through his own imprint, Diagonal Records, founded in 2011 with Jamie Williams, he issued a string of raw and impactful releases which saw the label become fertile ground for artists such as Shit and Shine, Russell Haswell, and Not Waving - all bound by the same pioneering spirit. Since then, his practice has only widened and deepened, working in collaboration with photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, to release the record “Spoken by the other” under the name ‘Powell Tillmans’. “Piano Music 1 to 7” released on independent experimental label Editions Mego, “a folder” a multimedia audio-visual project, a kind of archive of sound and image, and “26 Lives” recorded in collaboration with the London Contemporary Orchestra at the Barbican Centre. The breadth of his output is remarkable, and representative of an artist who has become a cornerstone of forward thinking experimental music.

Interview recorded at KEF Music Gallery, London. Friday 3rd October 2025

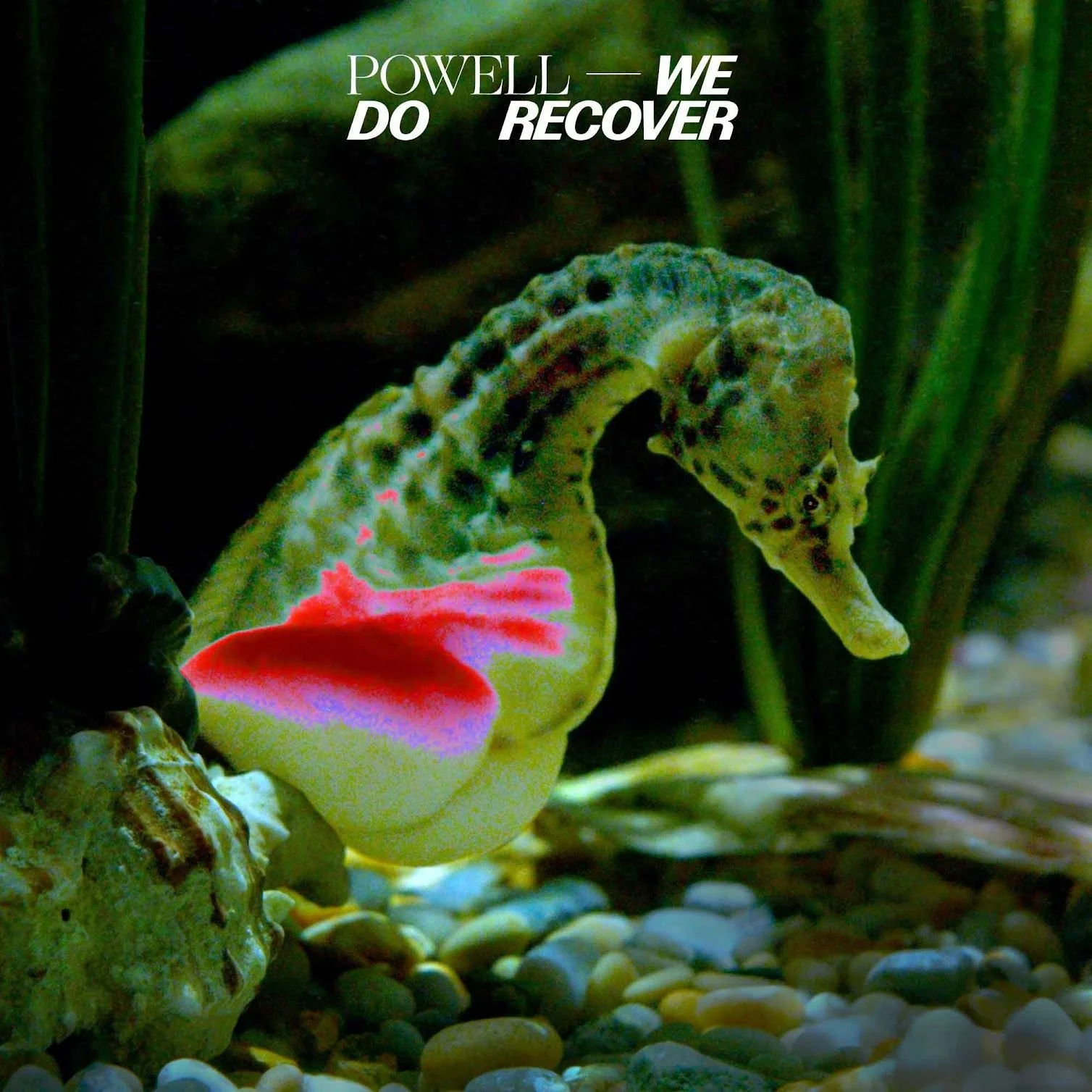

Cantwell: So, we're here today at KEF Music Gallery in central London with these two Goliath speakers in the room with us to talk about your practice and new album, We Do Recover, which is available now and released through your label Diagonal Records. I'd like to start there. This is the first time you've released a Powell album on Diagonal. Why is that first of all and what is the significance of releasing your album on your own label?

Powell: I think it was a combination of factors really. Like I did EPs on my label when I was young, just starting out, throwing stuff out there in the world and those kind of some reason, people loved them. So, things changed rapidly and, you know, suddenly I was in touch with big independent labels and XL recordings came calling. So I signed to XL which was brilliant for so many reasons not least because that's where I met my lovely wife, and they enabled me to do lots of really, interesting things obviously because you're supported financially and the influence they can exert over distribution all those kind of things. So when it came to doing a first album it was kind of like well they're going to pay me to do album, brilliant. And back then, I guess, having grown up buying twelves and dance singles and stuff, the album format was not something that came naturally to me. I was less an artist back then, I think and more a producer. So, I was producing twelves and this kind of thing. So, the idea of an album was this great sort of mythical thing, I guess. So it had to be on XL, and so that's the way it went. Then as my practice have changed over the years and albums have become different in their construction for me. They're not these great things that are going to signal how brilliant and amazing I am anymore. They're personal explorations for me that take me down all sorts of weird rabbit holes, you know? What I've learned is for an artist like me that makes the kind of music that I do, I don't need a platform like XL. I love XL. They're family. Got loads of friends there. Like I said, my wife's from there, but we don't as artists, we don't need this. It's enough for me to make a record, put it out, know that some people have listened to it and loved it and move on. And really that's my motivation for keeping my own record label going such that I will always have an output of some sort, the thought of not having an output. And it makes me sad when people send me records saying, "Please put this out" because they don't have they don't have that, you So, it's it's a it's a precious thing to try and keep alive. Even if the label makes negative money, always hasn't. We've never made any money from the label. You know, everything is everything costs us. That's why we that's why we all have day jobs now. You just can't sustain this life as a musician, unfortunately, that easily.

Cantwell: You talked about XL and your debut album being released on that platform in 2016. So it seems like since then, until now, you've trodden quite a different path to what some might expect a music producer or performer to take. Gravitating towards projects for example like "a folder". With the new album, is that for you a return to something that's quite familiar or does it feel like something new entirely?

Powell: I think it's more, it's a return to SPORT in so much as I feel like this is music that will connect with people. More than some of the things I've been doing in the meantime. But equally, it's a record that would only been I would only have been able to make had I been on this long-winded, divergent journey, I suppose, via a folder because in that, I guess after sport, the intensity of being on the front on the front line touring all the time, a lot of lot of pressure, even if it wasn't actually there, my mental health has never been particularly stable. So I found it very difficult to deal with that expectation making people move selling records always being there but being this constantly outward personality and I and that was who I was for a long time. I was very sort of upfront and I kind of provocative and I kind of embraced it but it in all honesty it wore me out and it kind of drove me inwards. Hence the journey the music going inwards as well and me wanting to find a folder was a very conceptual idea in that it allowed me to a build a folder around myself a sort of bubble and just do what I wanted. But it was also a conceptual idea that allowed us to just bucket bits of things that we were working on into various folders, and I always described it as being the folder as a refuge, after years being exposed to so much and people expecting certain things of you. I found it a relief to be in a space where I could just do what I wanted again. And I didn't release the first 12" till I was 28. So that's 13 years of just making music because I love making music. And during that time I'd made every everything from jungle techno to noise to computer music to all these things. And it just so happened at that time the records that people liked when I sent them to people were these sort of post-punk inspired ones because I listened to all sorts of music and happened to make these post-punk ones you know. And suddenly everyone's like, "Oh, there's this great post punk guy", and I'm like, well, okay, I like that music. I was influenced by it to make these tracks, but it's not just who I am at all and never really has been. I was never a punk. Far from it. All I was just trying to do is put a sort of electronic artist spin on some of those sort of things, the sonic things of that kind of music.

Cantwell: I was going to ask about how you felt being labeled or categorised in alongside those genres. Usually artists don't like to be pigeonholed in that sense, but for you was it a compliment to be?

Powell: It was at a time because I was such an electronic head from London, it was all just clubs and stuff like this to suddenly be thought of as oh industrial is punk, all these post punk or all these references to music that I'd really started to admire a lot. It was exciting, but I think I always felt that wasn't truly me. So, that did probably create some kind of divider between me and those communities that do exist around I never felt part of it to be I felt quite separate and I felt quite anxious to either be accepted or to find something else. I ended up going down the latter route to be honest. I still love all that music, but it's not it doesn't define me like some of the people who make that music their lives.

Cantwell: No. And I think when you draw influences and you're creating something at the time, it might be at that specific moment you're influenced by a particular sound or it might be a song or a person. And then you put that into the work and then all of a sudden you're labeled as being the resurgence of a whole genre. It's a heavy burden.

Powell: Exactly.

Cantwell: You've been very honest about the catalyst for this latest album being the friend of yours who took their own life and it's a tragedy and a loss in any case and when anyone takes their own life. So in respect to his memory, his loved ones and you. Do stop me at any point. You said "It made me see music that I had been making through a different lens. One that mirrored my experience of recovery. It's not linear. It's often difficult, but there's beauty in there if you look hard enough." From your current vantage point, how are you understanding the process of grief and recovery?

Powell: It's tough. I mean, it's really hard. First of all, there was obviously in my head I wondered whether it was appropriate to mention this kind of stuff in relation to a music in music because it's very easily for cynical people to be like he's exploiting this situation for his own ends or be sensitive to the family. Of course, I see them all the time. They're my best friends. Um, grief. I think to be honest, I'm only just starting to feel it to be honest. And I think this record has helped me get to that point. When he first died, and I've known this guy for since I was 12, so it's 30 years. I was unable to process it because I was always running away from things emotions with things like drugs, alcohol, anything but to feel. And his death then triggered in me a desire, I suppose. Nothing good can come from these things, but sparks, I suppose, of light can emerge. And I was able to then see that I needed to do something about how I lived my life in that respect. So I then entered a period of sobriety. And that gave me the clarity to then, because I've been very fortunate for like years. I hadn't had a full-time job. I was just making music, making music, making music, all day, every day, like non-stop. It wouldn't stop. So I have archives and archives and hard drives full of stuff. So with that perspective on grief and this desire to feel, I suppose, and to maybe use emotion in my music again or to express some kind of emotion. It allowed me then to look back on a lot of the things I made and to see that hang on that perhaps there's a story here. And I didn't want the story to be about me recovering from drug addiction because I don't think when I ever recovered and my journey is far from perfect, you know. I still struggle with it. Thank God not to the point that I was before. But I didn't want this to be a record about addiction and I didn't want it to be a record about my friend. I just wanted it to be a record of hope for anyone, in life, I suppose. I wanted it to feel positive, uplifting, and ultimately optimistic because I do find there's a lack of that thing in the world. I do find that perhaps in music as well cynical. There's a lot of I don't know, there's a lot of posturing. There's a lot of untruth and if I could just do something that's true and pure for me, then that would be enough and hopefully enough for someone else as well.

Cantwell: Yeah, you mentioned the word optimism there. I think listening to We Do Recover, just as a title, it's a statement of assurance. I do think you hear that in the record. And as you brought the album to completion was holding on to that sense of certainty was that an important part of the process?

Powell: Holding on to certainty, or the certainty of that there is an optimism in it?

Cantwell: Yeah, I think it's that self assurance, that reassurance to say "we do recover", rather than posing that as a question.

Powell: Yeah. Well, that's funny. I used to joke with my friends. “We do recover” is for anyone who's ever had to go to meetings, you know, NA meetings, narcotics anonymous meetings, it's one of the readings they read out is called "We do recover". And I always sat there listening to it even if I listened to nothing else in the early days of going to those meetings and thought there was something collectively beautiful about that statement like you said we as a collective it's not about I or me. And obviously we live in a very eye oriented world. So I love that sense that we can get better together. But as I would struggle with drugs and, you know, relapse and do stupid things and make mistakes, I would joke with Jamie, my friend who runs the label with me or my maybe I should call it “We do recover?”, like, question mark, you know, like when Ron Burgundy reads out, I'm Ron Burgundy, he's written a question mark on his teleprompter. "We do recover?"

[Laughs]

Who knows if we do recover, but one hopes that we can. I think that's all. I think collective optimism is certainly what I wanted to put into it.

Cantwell: One thing that first struck me about the record listening to it is there's a kind of monastic almost religious through-line to some of the songs especially in their sound. I think for me I was brought up in well around the Catholic church. So it might be that I'm particularly tuned to that kind of thing.

Powell: What does that mean? A monastic sound.

Cantwell: I think churchy, basically. And it's funny because when I thought about your work you mentioned, around the time of SPORT was released that, "I don't want to be in a church" is what you said in relation to the sound of that record.

Powell: In reverb, and use of reverb?

Cantwell: Exactly. Which I think can often, it creates space, doesn't it, in terms of sound? Does with the more kind of reflective moments on the album, "All These Feelings", "we glimpse a world", "Afterlife", is there a spiritual influence going on there in that sound, or are you still avoiding churches?

Powell: I'm fascinated to hear what people pick up in the music now that it's out today. I mean hopefully I'll hear a bit more about it. But I would agree with you. There is a spiritual thread for sure. Interesting. The church thing. Yeah. Someone else said something similar.

Funereal was one of the tracks as well. And I think there is, although it's all synthetic, some of the tones I used did start to sort of feel almost on the verge of an organ, and these quite sort of like heavy monastic tones. I'm going to use this word monastic more now.

Cantwell: It's a good word.

Powell: But, spirituality, I think, yeah, I think so. It's something I turn my nose up having had a church-based upbringing as well myself. Now every morning I look up to this sky and say, help me do what I need to do. Help me be the best person I can be today, or help me not be a twat today basically and it helps me even just pausing for five seconds and just thinking and letting it go, I suppose letting all this like, mind stuff, that happens with me and a lot of us today, I think just to think you can't control it, you can't control it, let it go and let someone else take care of it. Yeah I think that's true.

Cantwell: And the record was created over a period of 7 years-ish. So from 2018 to 2025. How have you seen your style in that time or kind of musical vocabulary evolve? And do you feel in some sense that you're working with the same tools, the same instincts as you were seven years ago? I mean, I guess in your mind you could compare one of the tracks that was maybe more recently finished versus one that you started in 2018. So, have you do you see that change or do you hear that change on the record?

Powell: Prior to 2018, I'd kind of run out of inspiration in terms of all my inspiration was constantly coming from other music. You know, talking about post-punk influence and sort of being influenced by strains of music and I found that limited. So when I was developing the folder project and stuff, I started to draw more on my love of film, my love of reading, started to find ways of being inspired musically by writers, philosophy, books,, some I suddenly found these things could inspire me way more than any piece of music ever could. So that then enabled me to develop creative processes such as like stochastic modelling like making music from probability. So using systems to generate shapes. So I'm never whereas previously I would be organising things on a computer. Now I'm just building a system that allows these things to unfold. So it's different to random because you're creating the likelihood that things will happen. You got a lot of control over that. That's and I think once I'd mastered that or as much as you can from around 2018 all the music started to be made a bit like in that in that style. So I don't think any of the music feels rigid at any point or you know what's going to happen next. It feels organic like a life form unfolding I think. That's true of all the music I make now has been for the last seven years. So there isn't that much difference to me between the music it was just about piecing together the story and that in itself took a year so it took six seven years to generate all sorts of music only a small chunk of it came on and that process of a year of compiling telling a story was a really amazing thing that I've never really taken the time to do when I made XL SPORT it was just like here's bangers and think that will do, let's go, whereas this was like almost more painful and difficult to find the way for it all to live together.

Cantwell: I was going to ask about does it take the same amount of energy to get each track finished and out into the world or do you struggle more with certain tracks than others? Does some sit not finished for a long time? How does that work for you?

Powell: Yeah, some do. Some are finished and that's it. But I think when it came to put the record together, then they had to be relooked at sonically, loudness levels, EQ processing and flow to make sure it was never there was a few tracks I just couldn't finish. I mean, they were finished, but it was just like which part where which why is this not working? This the smallest little things would upset the story for me. So I historically I would find things hard to finish because I'd have tracks in Logic or you know sample based music and stuff and it was just a nightmare. Whereas now because of the way I work it's spewed out and then I might process it and then and then it's basically done. So it's less about it less time to make the music now but more time to think about where it should go.

Cantwell: And I want to talk to you a little bit about ideas because it sounds like a lot of your ideas are formed around the process of actually making the sound and finding something interesting and then taking it further. And that there was a David Lynch quote that I quite liked where he says, "If you catch an idea that you love, that's a beautiful day." How do ideas arrive for you? Do you have like a romantic vision of inspiration or is it something that's a bit more technical?

Powell: I think it's more towards the romantic thing. When I started to look for new ways of working, I could look at a I could look at a tree and I could look at or I could look at like the surface of some water or the shape of a sky, a natural like mountain on the skyline. I started to be so bewildered and inspired by the infinite nature of nature, you know, where nothing is, how leaves distribute when they fall, all those kind of things. So that's why and I think that was triggered by a lot by reading a lot of Xenakis' readings about creating music based on the sort of infinite scale and beauty of nature. These kind of awesome massive things created by this basically the same probabilities and systems that generate the way the world is. So for me suddenly looking at a wave and stuff I could be that would make me want to make music for weeks or going for a walk with my dog that would open up whole new vistas for me as well. So it was very rarely like I'm awful technically basically, it's not like I go, I've got to get that module because I know it can do this and that. It's like I see something and then how can I use that and what am I going to do? Luckily I have people around me who give me the instruments I need to bring the ideas to life. A few anyway, like ALM busy circuits guy. And so I'll go to him and say, "What do I need?" And he said, "Use this." So I don't have wall to walls and modulars. I have the things I know how you can use and that's it.

Cantwell: And then this more kind of universal romantic vision of ideas and inspiration, is one side of the puzzle I guess, and then the other being discipline in the studio making the thing, recording the thing. How much of your practice is about discipline, routine and structure? And how much of it is about abandoning all that and letting things happen by accident and digression?

Powell: That's really interesting because well, so like I said, for the last years, I was incredibly disciplined. I would wake up, my wife would go to work, when she came back, I couldn't believe it. There'd been a whole day and it's another day in the studio. And that was me for 10 years, literally flat out. I wish I could have appreciated that time more, so rather than being like, why is no one booking me or, you know, I wish I could have been like, wow, to have this much time to generate music and be creative is one of the great privileges you can have in life. I think now I've got a kid. Making this kind of music doesn't pay the bills, unfortunately. So, I've had to go back into full-time employment. I have a different relationship with making music now. At first I was resentful. Now I'm comfortable with the fact that there will be more time ahead to generate. But really my relationship with creativity now is finding pockets of time where I can look back on the things I made and think there's something there. I can start to build stories out of the things I've made. Which was very much how We Do Recover was made. It wasn't like last year I was making new stuff. I was just listening. And that's a different relationship with it. I hope I can have another years where I can just sit around, listen, make music, and get stoned. Shouldn't have said that. Don't do drugs.

Cantwell: No comment.

[Laughs]

So when you're in the process of creating, do you have any sounding boards of people or references around you that you would consult with or are you always consulting with yourself?

Is that something that's quite in you and quite logical? Is it a logical part of your brain or is it something more intuitive struggle with that?

Powell: I have done historically. So I always envy like Rob and Sean from Autechre or something where there's two of them and they can say this is good. When I was younger, more immature and less able to deal with my emotions, I would frenetically send to people, you know, the my circle around me and friends and because I needed that affirmation. I constantly needed affirmation for my music, otherwise I thought it was useless. Now that sort of I got I don't need that anymore. So I've learned to be comfortable with the things I make and I feel like I've now got the ability to see what's good and what's not. And my wife occasionally I play her stuff, but she always jokes. She always jokes, "Oh god, do we have to do this now?" Because she knows historically back in the day if she didn't react a certain way and be like, "Wow, this is incredible." I would go off a cliff and into some kind of depressive cycle, you know? So, I needed that so much. But I learned that from other people like Russell. Russell Haswell for instance. I'll occasionally send stuff to him because I've always appreciated his influence and he's always helped me out. But you don't need to send it to them. Once it's done, it's done. You know, whatever. Who cares what other people think? That's the most important thing.

Cantwell: I think that's typical of your whole catalog and the kind of style of music that you make is that there's a bravery behind it to create, not necessarily challenging sounds, but challenge the way people think about sound. And that's going to make it particularly difficult in a kind of peer assessment setting like you would at Art School where you have kind of your peers criticise your work. That there isn't that standard really. It's not easy listening basically. If you're going to play it to a friend or your wife or whatever, that the reaction that you'll get from them isn't necessarily going to be one that's 100% positive. And I think that's the point of the music that you're making is that it's got more depth and more emotion than, "Oh, that's nice", you know?

Powell: I think so. Yeah. I mean, sometimes I was deluded though. I even sent XL the folder stuff, which is literally just like computer music. Thinking it was like really listenable. And then when they said no, I was like baffled and baffled and hurt. Peer assessment, it's nice when people like your music, but you know how people how the music world assesses me now is one of those things I can't control and I don't try to. But I do find it bizarre where the people who once supported me avidly, curators, distributor shops, these kind of things, then they no longer do. You know, it's a strange music world out there where it's the people who support you are not are often not truly your friends, they're just in it for themselves. If you can help them, then they'll try and help you. But Boomkat, for instance, described my folder work as unlistenable and they basically made my career and now they don't reply to my emails. So, it's sort of like that kind of stuff's painful to deal with as a young human being trying to make their way in something as difficult as music. Things are cool, you know. I love Boomkat. They're amazing what their contribution to experimental music. But these things hurt and any festivals that you used to go to and you present a new idea and they don't reply to your emails. It's really hard. You have to make your own way as an artist. No one's going to help you.

Cantwell: And I want to touch on a couple of influences that you mentioned potentially outside of music. Is there something in your life right now that is likely going to have an impact on your next work, do you think? Is there something that you're digging into at the moment?

Powell: I mean, I think subconsciously probably. It's hard to know what it is. I do feel my wife and I do spend some a lot of time sometimes digging back through my old work and stuff and I feel like maybe there's going to be a return to some more rhythm and dance oriented stuff just because it's a good way of me looking back through that archive of stuff. I do love that side of electronic music. That's where I was grew up, it was dark clubs, loud music. I loved it. And for some reason I think I retreated away from it because the mental health stuff and I found I just I needed something else at the time but I would like to go back there. So there's a possibility of that. But equally I don't know what it is yet. I got too much stuff to get through in terms of getting the stuff I've already made out. What I really want to do is just go to Cornwall and sit on a field in a tiny house with just some speakers and me and my dog and spend two months there and then I see what comes out of that. That's when I tend to work my best when I have the space when I have the space. Unfortunately, it's so hard to find.

Cantwell: And you touched upon club environments there. And you've talked about in the past about how you're happy to play your music in the space that it was designed for or that it was made for. How does location shape your ideas, whether it's a studio space that you're working in or the venue that you're performing your music in? How do different environments bring out different aspects of the work for you?

Powell: Do you have spaces in mind when you're making tracks? Honestly, I don't think I do really. I do when obviously there's like a multi- channel system available or when I went to the Xanakis 100th birthday thing at Kraftwerk in Berlin, then you start to really think about the space and how the music could work in the space. But other than that, no, not really. And I think it's a hang up from I think how I always consume music where I was never really a live music person. I was always just in my home my room listening to records on my turntables or listening on headphones and that just that was enough for me, you know. I never really when I create I'm not really thinking beyond that spatially. I would love to be able to do more of that, but no.

Cantwell: And I read this week that Corsica Studios in Elephant & Castle, South London is closing down. And that's a space that's meant a great deal to many. Do you feel like there's a need to protect these kinds of venues? And more broadly, how do you think about the fragility of music spaces at this moment in time?

Powell: I think it's so sad. I really do. I mean, I think Corsica might be finding another home if I read correctly. Jamie Shearer, he's managed that place. He's a friend of mine and I've been going there for what 20 years probably. I've done loads of Diagonal nights there. But it was like this. I remember in London like it's just terrible. How can a city of London with all the space it has not fine space with these kind of venues, it's extraordinary. Back in 2005 or whatever when we were going to forward they would do the occasional warehouse party in East London if you're old enough to remember. Might be middle and those kind warehouse and I remember thinking and talking to some of the people who were organising that how much it cost and stuff and even then it was almost impossible to find a warehouse and that was what 20 years ago, is it really since then? So it's been a problem like this in London for ages I just I just don't I just don't I mean I do understand it because London is just prioritises the wrong things because it's impossible to even live here, let alone play interesting, dynamic, forward, forward thinking music, so it doesn't surprise me. And but I do think it's so sad. I really do. It's such a shame. And Eclectic closed last year. That was a great space for experimental music. I don't know what the answer is. I'm no politician, but it's devastating. But it reflects the priorities I think we put on culture to be honest. You know it's the same for being an artist, it’s impossible for artists to live in this country as well as compared to other countries where they support you financially or whatever. It's we're just being squeezed but culture and society at large doesn't put a value on our and the individual who makes it. They actually tend to put a value on the people who collect it together and bring it together. So, streaming platforms, curators, it's always the ones who have a point of view on what's good and what's not and assembles it all together that can make a job of it or make a life of it. Never the people who are actually generating the stuff. And same for DJs. DJs just bring other people's music together and it's great, and I love DJs and I was a DJ, but now everyone's a freaking DJ and that was kind of why not really that I just got sick of it.

Cantwell: Yeah. And you say you're not a politician, but I think in regards to your music, there is a real counterculture statement being made in a lot of what you're doing. And, by no means would anyone expect you to be a politician, but you talked about your move away from DJing and that being quite a conscious decision for you. I also want to touch upon collaborations because that's become like an important part of what you've been doing in recent years. How did projects like Powell Tillmans and "a folder" come about? And what is it like working with other artists?

Powell: I love it, to be honest, when it's the right person. The Wolfgang one was a sort of XL things. I was still working with XL at the time and he had a connection with XL and we sort of met at his show at Tate Modern at the time and we just started talking throwing things around and we just had a natural connection as human beings I think, which helped. And yeah I think he learned from me and I learned from him a lot. I loved working with Wolfgang. We're still we're still great friends today. It was funny because he was obviously nervous about entering into the world of music, being like a superstar, you know, one of the great living artists to then have his reputation potentially under threat or to be judged and stuff. It's a big bold move for someone to do that and I really respect and admire him for it. It's not like he's just come into music and then disappeared again. He's fully committed and music runs in his blood. So in that sense it was really easy and there was a desire to do something special. The other one with the "folder" has been now going for five or six years and they're still working with me today. That one just happened so naturally. He actually does a lot of film work for Wolfgang. That's how I met him. Marte Eknæs is an amazing Norwegian visual artist. And we just started talking about the kind of themes that we were interested and a lot of the same sort of philosophical ideas I suppose were we had a lot of overlap with and it just felt very natural and very easy. Because we all have very different skill sets, me music, then visuals, sculptural stuff there was just a natural synergy basically and we were all just starting to fill in together.

Cantwell: Yeah. It's like you found that band environment almost.

Powell: It was like a band. Like nothing like no band ever made. Yeah.

Cantwell: And tomorrow when this is broadcast you'll have played your headline show at the ICA in London. Tell us a little bit about that show and who are some of the people involved.

Powell: So yeah it's at the ICA which is always a great honour I think. I mean the music programming over the years has sort of been up and down I think a bit and they've been doing some really good stuff recently and they put a d&b audiotechnik sound system in there and obviously they do they do great they represent great art and an institution of contemporary art in London. So they're amazing and yeah we were asked to do a night there. I'm always so terrified about doing an album launch or this is me. It's all about me. So I very much wanted it to be a sort of shared a shared perspective on the label I suppose.

Cantwell: So Florian Hecker and Martin Pietruszewski. Florian's music when I first heard it kind of changed my life. I don't know if you know his music? It just sounds like another world. It completely opened up a whole new vista for me. And Martin Pietruszewski works in a very similar field working in kind of computer music and so they're coming together for a collaboration that translates graphic systems into audio and stuff. That should be cool. And then Russell Haswell and Regis are coming together for their concrete fence project. And Russell is obviously kind of been like my brother in arms through music the last 15 years. And Regis is nice because he was the first one. That's how my music life career started. I don't know if you know, when I handed him a handwritten CDR at one of his little gigs thinking nothing would come from it. And then he rang me the next day and did a remix for my first record. So, it's a kind of nice coming full circle kind of family thing.

Cantwell: And you've mentioned kind of a move away from DJing, a move away from the club environment. You've stepped into the art world, I'd say, in many respects, and I think the ICA is a good example of that, where it's part gallery space, but also has a venue within it. How does the art world influence your work? And is it more that your music naturally finds a home in those spaces now, do you think?

Powell: I don't think the art world influences my work as I kind of would love to. I don't know. Do I want, am I part of the art world? Am I not? I don't really know where I belong. I think, I can't control it. What I do find is that I enjoy playing more art based spaces where specifically where an audience can be more open-minded when the spaces could be configured in different ways than just like a stage, and a club environment. I don't know. I try to think of myself as an island rather than being part of anything. I think that's where I feel most comfortable. Again it comes back to that folder thing. Like for instance, I don't really listen to any other music right now. I haven't done for 5 years. I don't know whether it's something to do with my medication, but music for me is my way of getting out what's inside me really. I say to my wife very often it could have been anything else. It could have been making film. It could have been a gardener, or the thing that I do to make myself happy. Basically that's all it is. I mean for a long time music was just like a drug for me like an escape. It was my life was in chaos, but I could go and do that for 10 hours. So it's something very precious and very personal to me but I always think my relationship with music is completely different to other people's in some ways. I'm not thinking about how can I get more into the art world. I'm not thinking about who my music sounds like. I'm not listening to other music. It's enough for me what's in here. What I get from my family, what I see around me, and that's it.

Cantwell: You've mentioned there about kind of crossing disciplines and being influenced by things outside of music, and your recent work has been accompanied by video, photography. Are there any other fields that you're interested to explore further? How far could you go do you think?

Powell: With the music?

Cantwell: Yeah.

Powell: I mean I would love to do film soundtracking and stuff. Well, I mean, would I? I'm not very good at being told what to do and there would invariably be a large chunk of that unless you happen to find a director who is willing to let you do go carte-blanche. All I want to do is just make things and put them out in the world. The format will involve. I mean, if you look at what my life my artistic life so far is, it is always changing. I never predicted that I would be doing these things 10 years ago. So, I would hope in 10 years I'm doing things I never would have dreamed of. There is an artist friend who works with stone who's got access to this quarry in Italy and stuff that we've talked about doing mass massive scale installations sort of out in nature and those kind of things are really exciting and I'd love to do that kind of stuff. Just got to sort of get my boy stable, safe into school and then I can maybe think about branching out again. And I've got to try and stay healthy as well.

Cantwell: Absolutely.

Powell: You can't do all those things if you're dead.

- End -

Powell’s We Do Recover is available to buy now on Diagonal Records.

With special thanks to Diagonal Records

Oscar Powell

Jaime Williams

John Cronin

Guy Featherstone

Marte Eknæs

Michael Amstad

Tyrone Smith

KEF Music Gallery, London

Samara Wilson

Mariam Nadeen

Linda Yau

Geoff Loveday

Apple Podcasts: Powell: New Music, Recovery and the Art of Letting Go

YouTube: @boundaryinc

Instagram: @boundary.inc

Substack: @boundaryinc